Early Christian and Byzantine Manuscripts

Before the book, there was the manuscript. I’m talking medieval manuscripts, those ancient tomes associated with dusty monasteries and devout prayers. In fact, most European medieval manuscripts were made for religious purposes, and the first known manuscripts, or codices, are early Christian. The codex was developed in the 4th to 6th centuries C.E. as a means to carry and read texts in an easier way. In ancient times, scrolls and tablets were the common way to go. With the coming of the evangelic Bible, other means were needed to carry the Christian message across the world. The codex was lighter than a tablet, and easier to read than a scroll. It was also made from parchment or vellum, which lasted much longer than papyrus, the material used for scrolls. There are scientific, philosophical and mythical texts written down in manuscripts. However, by far the most manuscripts of Medieval Europe contain texts from the Old and New Testaments, or other Christian texts.

Manuscripts were costly to make, because they were made from parchment. This was no drawback for a long time, however. Reading was something only educated people could do, and only the rich elite had the means to educate themselves. Tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of manuscripts were made during the Middle Ages. Many of them were text-only, but more than enough beautifully illustrated codices have been preserved. These illustrations are known as illuminations – they enlighten the text in a manuscript. Beautiful colors were used, sometimes even pure gold! These precious manuscripts were not simply made for reading. They were meant to be shown to guests, relatives and rivals, during church masses or in kingly courts.

Art is never made in a vacuum. Considering the earliest manuscript illuminations were made in the era of the late Roman and early Byzantine empires, their styles are based on the artworks already known in this period. So it is that the illuminations in the 5th century Vatican Vergil look a lot like Roman murals. This includes the suggestion of a landscape and a red frame in which the illustration is caught. It acts as a sort of window through which the viewer can watch the scene. Text and illustrations are clearly separated, but supplementary (though the illustration is made in service of the text).

Other well known manuscripts from the early Christian and Byzantine era’s are the Vienna Gospels, the Rabula Gospels and the Paris Psalter.

Insular manuscripts

In the early Middle Ages, some monasteries became important centers for manuscript production. In the 7th-9th centuries, the British Isles (especially Ireland and Scotland) held a great reputation. They produced some of the most famous manuscripts of medieval Europe. Perhaps the coming of Christianity can be equaled with the coming of the book in this area, because books were virtually unknown here up until that time. The larger manuscripts were especially made to impress people and excelled in doing so. They were meant to be used during mass and to carry around in processions.

The most renowned of the Insular manuscripts is the Book of Kells – it is regarded as the height of manuscript illumination in the early Middle Ages. Nowadays it can be viewed in Dublin, although it’s not sure whether it was made in Ireland, or brought there from Scotland by Irish monks. The style is a particular mix of Insular and classical motifs, as can be seen on its most famous page, the Chi-Ro page. This page, starting the gospels of Matthew, depicts the Chi and Ro, the first letters of Christ’s name spelled in Greek. The initials and decorations have swallowed the whole page. Everywhere one looks wonderful details can be made out.

Other well known Insular manuscripts from this period are the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Durrow.

Manuscripts from the Carolingian and Ottonian Empires

Charlemagne was the greatest Emperor of medieval Western Europa, and it is because of him that manuscripts were spread everywhere. Even though he couldn’t write and only learned to read later in life, Charlemagne understood the power of the written word. He gathered learned men from all over the known world in his court in Aachen. His court became a powerful cultural center for art and learning. Many manuscripts from many areas, religious and profane, were gathered and copied in his court school. One of Charlemagnes goals was to find the original true text of the Bible, because through centuries of copying the text had been corrupted. To write more quickly in a clear handwriting, the Carolingian Minuscel, was developed. This is the base of our contemporary writing and typing font.

The Gospel book of Godescalc was named after the monk who most likely wrote it, because his name was added in the pages. In this beautiful Carolingian manuscript, we see again a mix of Northern European elements and classical elements. The emphasis is on the classical aspect, and perhaps Mediterranean manuscripts served as an example for this one. The page shows Christ seated in Majesty on his heavenly throne. The way he is depicted show influences from Byzantine icons, though the linear, two-dimensional quality of the figure is definitely northern. The architecture of the heavenly city in the background has been reduced to a pattern. Everything is done in service of Christian symbolism – realism is not very important. Christ’s purple clothing indicates the might of a divine emperor. It might be an indication of Charlemagnes aspirations; he became emperor 20 years after this manuscript was made.

The Ottonian emperors followed in the power vacuum left behind by the Carolingians in the 10th century. Ottonian art can be seen as a mingling of Carolingian, Byzantine and Early-Christian art. Just like Carolingian art it was used for imperial propaganda and spreading the Christian faith. The Ottonian period coincides with a strong reforming and growth of the church. In this period too, beautiful manuscripts were made to further the goals of Church and Emperor alike.

The Gospel book of Otto III, made around the year 1000, is named after the third Ottonian emperor, for whom it was made. This manuscript is also lavishly decorated with bright colors and leaf gold. More emphasis is placed on representation, and less on decoration, making the illuminations even more clear. This indicates a strong tie with Roman and Byzantine traditions. The Gospel book contains a beautiful series of illustrations on the life of Christ. The example above shows Christ washing the feet of St. Peter. Note how the figures stand in front of a large gold surface, that envisions a wall of the heavenly city. Gold, which lasts eternal and stays beautiful, was often a reference to heaven and the divine.

Other well known manuscripts of this era are the Ebbo Gospels, The Utrecht Psalter and the Pericopes of Henry II.

Gothic Manuscripts

In the Gothic era making manuscripts had become a business of the court as much as of monasteries. At the court of the 13th-century French king Louis IX, beautiful manuscripts were made in his particular court style. Innovative illuminators incorporated styles and techniques from other art forms in their work. Thus the simple, round forms and clear colors of glass windows can also be found in manuscripts. The refined taste of the French court set a new standard for the rest of Europe. During a time when the Renaissance is being born in Italy, we can see little baby-steps toward more realism in Northern art too.

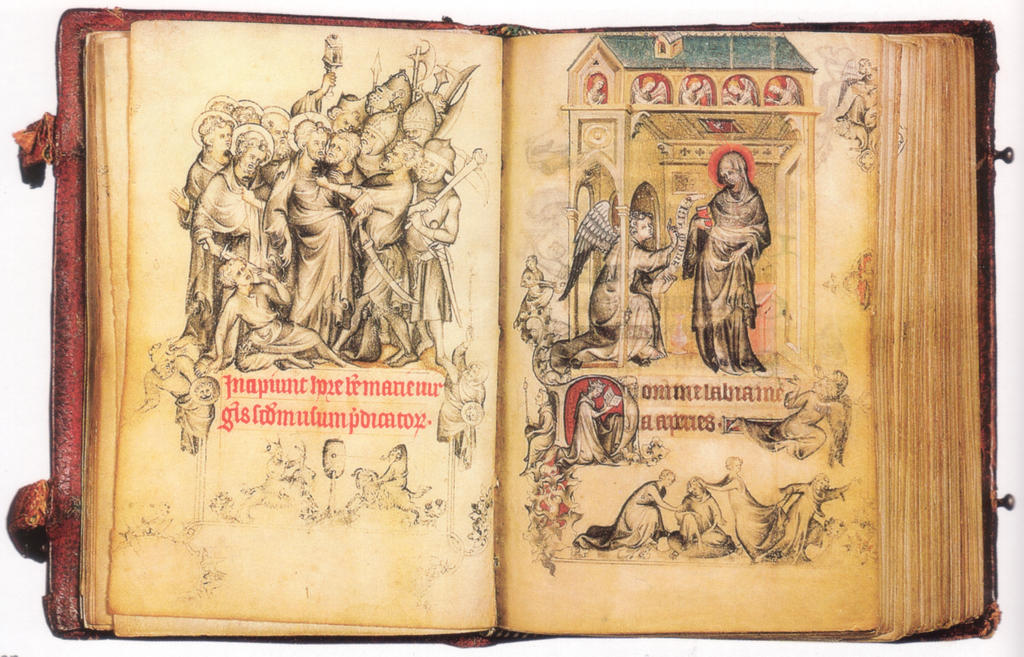

The search for perspective, illusionism and plasticity is barely visible in many later Gothic artworks, manuscripts among them. Look at this small Book of Hours, made around 1325-28 by Jean Pucelle for the French Queen in Paris. On these pages we see the betrayal of Christ on the left and the Annunciation of the birth of Christ on the right. A large part of the illuminations is made with the Grisaille technique. It’s already in the name – these scenes are depicted in grey tones, which puts the emphasis on shape and shadow. This is not Pucelle’s only innovation – he also practices the use of architectural space on a two-dimensional surface. The angel on the right page is standing in the portal, not beside or in front of it, as Mary is standing in the room. We can see perspective in the building, like the ceiling and the roof. Even though it’s by no means perfect, we have to keep in mind that these are the first depictions of perspective since the classics.

Well known in later medieval manuscripts are the many marginal depictions of frivolous scenes that don’t seem to have much to do with devotion. The kneeling woman in de capital D is queen Jeanne herself, while she is reading her Book of Hours. Amongst her are many other figures, such as knights riding fantasy beasts, girls playing a game, a squirrel, a monkey and a rabbit peeking out of its hole. The exact meaning of these drôleries (which is French for ‘jokes’) isn’t known, but they were apparently very popular, since they can be found everywhere. Sometimes, but not always, they give moral messages – think of the stories about Reynart the fox, or the Ship of Fools.

Other well known examples of gothic manuscripts are the Psalter of St. Louis and The Prayer Book of Philip IV the Fair.

International Gothic Manuscripts

In the 14th and 15th centuries the Italian Renaissance reached northern Europe. The English and Bourgundian aristocracies (among others) kept to their traditional style, which in this period is called the International Gothic style. Smaller artworks were very popular at courts, manuscripts being among them. Books of hours stayed ever popular in a time when personal devotion was growing. They were books that were made to guide a person with their prayers, engaging them in private contemplation. Even though these manuscripts tend to be small, the illuminations are astonishingly detailed and realistic.

The most famous book of hours, which is made in the International Gothic style, is the Très Riches Heurs du Duc de Berry. It was made by the brothers Limburg for the duke of Berry, an enthusiastic patron of the arts. He gave this assignment in 1413, but when the brother died all three in 1416 (probably because of the plague),it still wasn’t finished – the unfinished pages were illuminated by another unknown master. Well known are the calendar pages, which is a typical medieval tradition in which the twelve months of the year are shown with their corresponding zodiac signs and activities. On the page above the month of September is shown, with people harvesting in the fields. Here we see the refined realism of this era, in which medieval art slowly makes place for Renaissance art. It’s not so much an illustrations as a complete painting on one page. These sorts of illuminations had a big influence on the northern painting tradition.

Other well known examples of the International Gothic style are the Book of Hours of Catherina of Cleves and the Hours of Marshal Boucicaut.

Epilogue – The invention of the printing press

In the 15th century a new medium was invented: the printing press. Through this medium, texts could now be printed and copied. Illustrations too could be made through woodcutting or etching, and copied alongside texts. This way, a large quantity of one text could be printed and distributed among many people in a short time and for a relatively low price. Manuscript making, which was costly and labor-intensive, and which only geared one exemplar per process, slowly became obsolete. Today we can see them mostly in museums, antique libraries, and the occasional church mass. But our modern printed book would never have been here today if not for its ancestor, the manuscript handmade of parchment and ink.

Further reading:

Alexander J.J.G. Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work. Yale University Press. 1992.Davies, Penelope J.E. e.a. Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition. 7th Edition. Prentice Hall. 2006.

De Hamel, C. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. Phaidon Press. 1994.

Kleiner, Fred A. Gardner’s Art through the Ages: the Western Perspective. 12th edition. Thomson & Wadsworth. 2006.

Pächt, Otto. Book Illumination on the Middle Ages, an introduction. Harvey Miller. 1986.

Wieck, R.S. Painted Prayers, Books of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art. George Braziller & Pierpont Morgan Library. 1997.

Department of Medieval Art and the Cloisters in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. ‘The Art of the Book in the Middle Ages’ on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/book…

The British Library. ‘An Introduction to Medieval Manuscripts’ on the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts. www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminat…

![]()

![]()

![]()